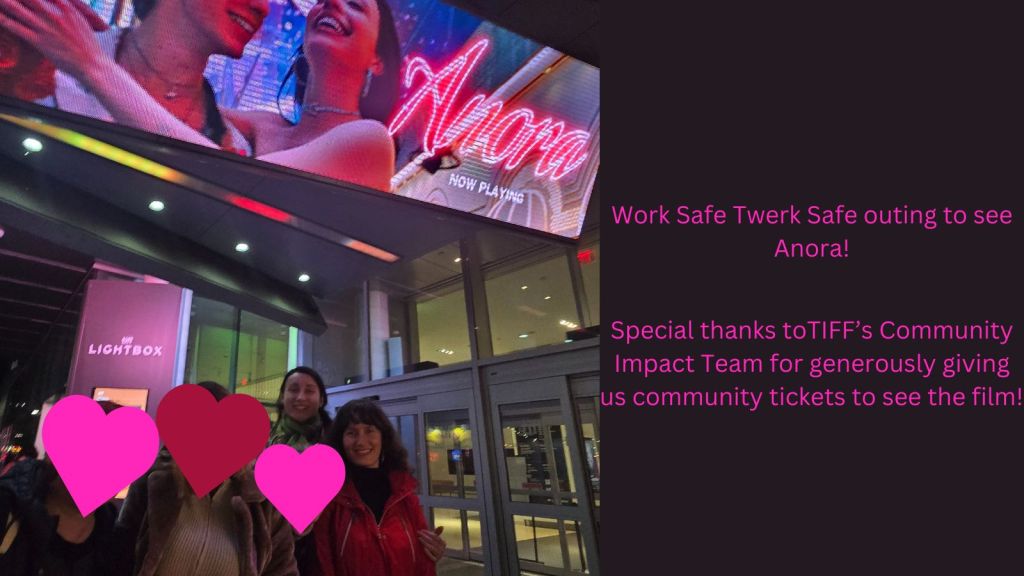

Thanks to free tickets from TIFF Community Impact, we got Work Safe Twerk Safe members out to TIFF Lightbox on October 29, 2024 to see Anora, a film about a sex worker who works in a strip club and occasionally sees clients outside the club as an independent escort. Without giving too much away, the titular character, Anora (who goes by Ani) is asked by the club manager to hang out with a customer because she speaks Russian; the customer in question turns out to be the son of a Russian oligarch who is partying in New York before he has to return to Russia to begin work at his parents’ company. Ani soon realizes just how wealthy this customer, Ivan, is, and makes it her mission to make him her regular. Things get more serious—and seemingly real—between them once Ivan hires her to be his girlfriend for the week. What ensues is a tragi-comical adventure, in which his family tries to intervene to put a stop to their relationship, and through which we see how significant differences in class privilege and socio-economic resources inform how people understand and relate to each other and the world.

An important and worthwhile spoiler, especially for our sex worker comrades out there, given the abundance of dead/violated sex worker gags and imagery in TV shows and movies (especially Rough Night, 2017, and Tina Faye’s pretty much entire oeuvre, same with CSI SVU): no strippers are killed in Anora, nor is it a film about how stripping (or sex work in general) is not a ‘real job.’ But there are several big themes in this film that often play out through stereotypical tropes of struggle or mental illness (e.g., Dancing at the Blue Iguana, 2000; Frankie & Alice, 2010) or overcoming-the-odds-by-exiting (e.g., Pretty Woman, 1990; We’re the Millers, 2013; Afternoon Delight, 2013; the Magic Mike series, if you think about it) or violence or exploitation (the Taken series) in popular entertainment representations of strippers and other sex workers: power, class, and gender relations; the servility of catering to the whims of rich clients; stigma and the violence it informs. Refreshingly, however, Anora does not stoop to stereotypes.

The strip club, which is shown from door to floor to VIP, is never painted as a locus of exploitation, nor are the dancers painted as victims or dupes. Instead, we see a variety of dancers (and boundaries and services being negotiated) and a variety of customers doing their thing. The club itself is also realistic: neither too nice (including the changeroom which is crowded and a bit high-school-locker-room), nor dreary and creepy in the way strip clubs are often shown or suggested to be. Management is, similarly, average: we see dancers complaining about the DJ being impolite and about their working conditions (unreasonable scheduling demands, lack of benefits), and pimps do not feature in the story. Even the sounds of the strip club are on point: the clacking of high heels, the chaotic background noise on the floor, the muffled music in the VIP rooms. In short, the strip club is relatably real—nothing about it made us cringe!

Particularly notable is how the film gets the nuances in our relationships with customers: Ani and Ivan both try to get the other to do what they want in ways that highlight the different resources they have at their disposal and the different degrees of strategy and creativity they employ to get their way. While Ivan seems cool and earnest at first, we see his privilege—and its implications—more and more throughout the film. But Ani is never depicted as a victim because of this power imbalance; she is resourceful, clever, scrappy, economically-minded, and most importantly, agentic and unashamed, even as she comes to care about him beyond the bounds of a worker-client relationship, and contends with stigma and vitriol from his family and their various associates and henchmen (whose servility to and reliance on their oligarch employers becomes increasingly apparent).

In recent years there have been some movies and TV shows that have represented strippers respectfully, and taking place from or showing their perspectives: Hustlers (2019); Zola (2020); P-Valley (2020-2022). Watching Anora, it was nice to see a film in which stripping, and activities and experiences related to it, just felt so normal, even as it embarked on a wild mis/adventure with a super-rich client. Here we might read in a message, if not explicitly for, then speaking to, strippers: being rich and fancy doesn’t automatically make someone a reliable or good client, person, or ally. It was fun to see the dollars and decadence while they lasted though!

Overall, Anora earns two thumbs (or heels) up!